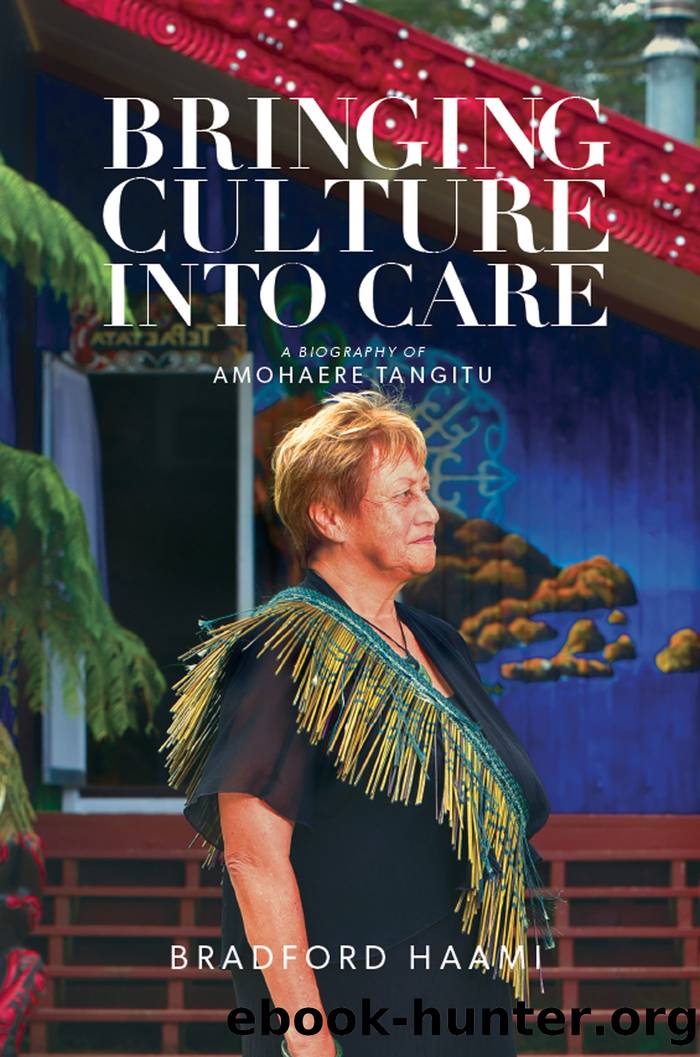

Bringing Culture into Care by Bradford Haami

Author:Bradford Haami

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Huia (NZ) Ltd

Published: 2019-10-15T00:00:00+00:00

NINE

Expanding Horizons

One group Amohaere greatly admired for their loving work with the children in Princess Mary Hospital and later at Starship were the grandparent volunteers. This was a core of ten to fifteen women who substituted as caring grandparents for those children in the wards who had no visitors.

âThey would visit the children daily, bathe them, read them stories and take them for pushchair rides through the corridors. All were PÄkehÄ except for one shy old MÄori kuia, Aunty Mate. She would search me out when she was on site, carrying the MÄori babies in her arms.â Amohaere applauded their work and saw great value in making strong relationships with these kinds of groups.

Te WhÄnau Atawhai functioned in a similar way, for the same cause, but from a MÄori cultural perspective. In its daily running, Te WhÄnau Atawhaiâs WhÄnau Room was frequented by MÄori elders as volunteers â kuia and kaumÄtua rostered to be on hand for the children and the visiting families. The order of the day always began with karakia at 8.30 a.m. followed by mihi, waiata and a briefing. These caring pÄkeke (elders) were essential to creating an environment of wellness, so much so that when children had to go home, many would cry to stay with them.

Volunteer kaumÄtua Brownie Williams saw the WhÄnau Atawhai unit as a âmini-mobile-marae stalking the wards of Aucklandâs hospitals, trying to ensure that the medical system is sensitive to the needs of its MÄori consumersâ.1 His role was as simple as âsitting at the shoulder of a patientâs relatives, giving them the courage to ask the questions they needed answered. It may mean calling MÄori outpatients who have missed a clinic appointment because they canât afford the transport and are too ashamed to admit it, then picking them up in a board car, [and] promising clinical staff, theyâre going to be late, but theyâll be here.â2

In addition to the pÄkeke volunteers, broadening the services of Te WhÄnau Atawhai meant finding more competent MÄori workers. Amohaere had been contacted by Mavis Tuoro and Toby Curtis from the Auckland Institute of Technology, who ran a kaupapa MÄori social services certificate programme. They were searching for placement opportunities for their MÄori students. Mavis had previously been unable to place students in the hospital social work department because there was no belief that her programme had the right accreditation to warrant providing placements. Amohaere sought the support of her ally Mary Futter, and it was Nurse Futter who was responsible for opening the door to kaupapa MÄori placements with the first student beginning in August 1990.3 From that time on, there were twice-yearly student placements. At the end of their allotted time, some of the students continued to volunteer in the unit. In time, when positions became available within Te WhÄnau Atawhai, they filled some of them.

Te WhÄnau Atawhai Annual Report for 1992 noted that staff in the unit consisted of four full-time kaiatawhai who worked closely with a team of kaumÄtua, kuia kaitiaki and volunteer kaiatawhai.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Hit Refresh by Satya Nadella(8350)

When Breath Becomes Air by Paul Kalanithi(7284)

The Girl Without a Voice by Casey Watson(7276)

Do No Harm Stories of Life, Death and Brain Surgery by Henry Marsh(6346)

A Court of Wings and Ruin by Sarah J. Maas(6135)

Hunger by Roxane Gay(4241)

Shoe Dog by Phil Knight(4194)

Everything Happens for a Reason by Kate Bowler(4079)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4047)

The Rules Do Not Apply by Ariel Levy(3924)

Tuesdays with Morrie by Mitch Albom(3853)

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot(3838)

How to Change Your Mind by Michael Pollan(3693)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(3585)

All Creatures Great and Small by James Herriot(3532)

Elon Musk by Ashlee Vance(3464)

Tokyo Vice: An American Reporter on the Police Beat in Japan by Jake Adelstein(3451)

Man and His Symbols by Carl Gustav Jung(3336)

The Money Culture by Michael Lewis(3300)