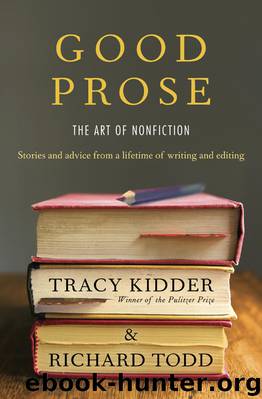

Good Prose by Tracy Kidder

Author:Tracy Kidder [Kidder, Tracy]

Language: eng

Format: epub, mobi

ISBN: 978-0-679-60472-3

Publisher: Random House Publishing Group

Published: 2013-01-14T13:00:00+00:00

This passage introduces the story of a lawsuit. The defendant was the writer Joe McGinniss, the plaintiff a convicted murderer named Jeffrey MacDonald. He and McGinniss had made a deal before his trial: he would give McGinniss special access to his life and to his defense team at the trial; in return he’d receive some of the proceeds from the book. Plainly, he expected McGinniss to portray him as innocent, and in the beginning McGinniss intended to do so. The two men became friends, but by the end of the trial McGinniss had changed his mind. He came to believe that the man had in fact murdered his family. But he didn’t tell his subject this. Indeed, he wrote him letters of sympathy even as he created in his manuscript the portrait of a monster. The letters are painfully embarrassing to read, and the murderer’s lawyer used them to powerful effect, as does Malcolm. In the end, the suit was more or less successful; McGinniss agreed to pay MacDonald $325,000.

This story could not be more perfect for Malcolm’s uses. Indeed the first criticism of her argument is the very perfection of the story it relies on. Hard cases make bad law, the lawyers say, and this is a difficult case, not the sort of case from which to draw sweeping generalizations about journalists and their subjects. And Malcolm makes no real attempt to see McGinniss’s side; her excuse, the lamest in the journalist’s arsenal, is that McGinniss wouldn’t talk to her. But whatever one makes of the merits of the lawsuit, Malcolm’s analysis has value—especially for journalists who wish that the matters she deals with had been left submerged.

Few journalists would condone lying in their private lives. And yet many nonfiction writers venerate In Cold Blood, for which Truman Capote appears to have lied shamelessly to his subjects. Maybe the moral standing of the person matters. Is it okay to lie to a killer but not to, say, a Rotarian? Most writers feel uncomfortable at best with Capote’s methods, and condemn them even if they celebrate the book. And what about less dramatic cases? What about those little gray areas? How much candor is a subject owed? If for example your subject makes a racist remark, which you would in ordinary conversation object to, do you let it slide by? Probably you do. Do you laugh at the unfunny joke? Nothing wrong with that, surely. Do you smile noncommittally when you hear an opinion you disagree with? If asked outright whether you agree with your subject when you could not in fact disagree more, do you give a little murmur that could be interpreted as assent? Perhaps you say, “I see your point.”

Malcolm argues that something dishonest tends to lurk in all relationships between authors and their subjects. Certainly, all such relationships contain competing narratives. The subject has a story, the writer has a story, and the two don’t coincide exactly. They may diverge radically. Writer and subject each want something from the other.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Actors & Entertainers | Artists, Architects & Photographers |

| Authors | Composers & Musicians |

| Dancers | Movie Directors |

| Television Performers | Theatre |

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(30934)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(30889)

Fanny Burney by Claire Harman(25784)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(18074)

Plagued by Fire by Paul Hendrickson(16637)

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(13868)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(13109)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(12750)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(11903)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(11050)

Adultolescence by Gabbie Hanna(8145)

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(7551)

Note to Self by Connor Franta(7024)

Diary of a Player by Brad Paisley(6866)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(5878)

What Does This Button Do? by Bruce Dickinson(5527)

Recovery by Russell Brand(4565)

Born a Crime by Trevor Noah(4511)

The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini(4435)