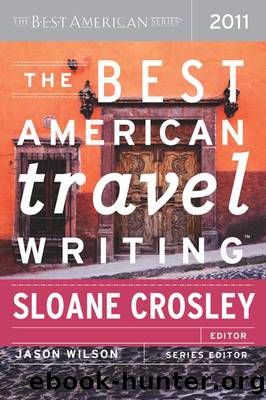

The Best American Travel Writing 2011 by Jason Wilson

Author:Jason Wilson

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: HarperCollins

Aside from three-card monte and Wall Street, Manhattan doesnât have much in the way of gambling. New Yorkers travel south to Atlantic City, or up to Connecticut, to gamble. Long Islanders take a high-speed ferry to New London or Bridgeport, near the Pequotsâ and the Mohegansâ casinos, the two largest in North America.

This maritime movement of business from the East End of Long Island to Connecticut follows a pattern established centuries ago. The currency that sustained the fur trade between European settlers and native people was wampumâbeads made from the purple interior of clamshells. The Shinnecocks produced wampum from shells found on the banks of Long Island Sound and brought it by canoe to Connecticut, where the Pequots, a more powerful tribe, controlled the local economy. Only when the Pequots were routed by the Europeans, in the Pequot War of 1637, did they begin trading with the settlers directly. A Shinnecock casino would, in a sense, renew that direct exchange.

The Foxwoods and Mohegan Sun casinos are enormously successful, and their earnings have transformed the Indian nations that operate them. Before the Mohegans started their business, they were a scattered group of mostly impoverished individuals. Now they are a model of organized prosperity. If you could use a scholarship, health care, child care, or retirement benefits, it is far better these days to be Mohegan than it is to be American.

Since the inception of the United States, Indian governments have been recognized as sovereign entities, exempt from taxation. But the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act of 1988 requires tribes to negotiate compacts with states in which they operate casinos, and those compacts almost always include a revenue-sharing agreement. Last year, the slot machines at Foxwoods and Mohegan Sun were the Connecticut governmentâs biggest private source of revenue, yielding $362 million. Foxwoods has eleven thousand employees, making it one of the largest employers in the state.

Once a tribe is federally recognized, it is eligible to open a casino, and the promise of wealth attracts financial backers to pay for the necessary builders, lawyers, and lobbyists. The Shinnecocks have been pursuing recognition since 1978ânine years before the Supreme Court ruled, in California v. Cabazon Band of Mission Indians, that states have no authority to regulate gambling on reservations. In support of their claim, they have submitted more than forty thousand pages of documentation substantiating their history and lineage. Meanwhile, tribes across the country have bloomed into thriving mini-nations, while the Shinnecocks, as Lancelot Gumbs, a senior trustee, said, have remained âstuck in the Stone Age.â

This summer, after thirty-two years, the Bureau of Indian Affairs declared that the Shinnecocks had met the seven criteria for federal acknowledgment, and that their petition had been provisionally approved; after a thirty-day waiting period, they would finally have tribal status. One of the trustees, Gordell Wright, described a celebratory mood: âWeâre going to be doing a lot of singing and eating.â But, a few days before the waiting period ended, a group calling itself the Connecticut Coalition for Gaming

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| African American | Asian American |

| Classics | Anthologies |

| Drama | Hispanic |

| Humor | Native American |

| Poetry | Southern |

Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan(8378)

How to Bang a Billionaire by Alexis Hall(7422)

Win Bigly by Scott Adams(6330)

Little Fires Everywhere by Celeste Ng(6161)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(5901)

Tease (Temptation Series Book 4) by Ella Frank(5012)

Pachinko by Min Jin Lee(4587)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(4357)

China Rich Girlfriend by Kwan Kevin(3907)

The Perks of Being a Wallflower by Stephen Chbosky(3835)

First Position by Melissa Brayden(3816)

Rich People Problems by Kevin Kwan(3786)

Bluets by Maggie Nelson(3731)

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen(3530)

Right Here, Right Now by Georgia Beers(3515)

Walking by Henry David Thoreau(3242)

Catherine Anderson - Comanche 03 by Indigo Blue(3176)

I'll Catch You by Farrah Rochon(3157)

A Little Life (2015) by Hanya Yanagihara(3153)