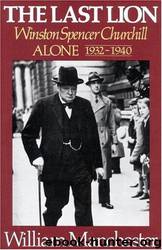

The Last Lion 02 - Winston Churchill - Alone, 1932-1940 by William Manchester

Author:William Manchester [Manchester, William]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: Biography & Autobiography, Historical, Political

ISBN: 9780316545129

Google: dP7-nQEACAAJ

Publisher: Little, Brown

Published: 1988-10-27T13:00:00+00:00

Clementine bathing in Chartwell’s swimming pool, one of Winston’s creations.

A life mask of Clementine, taken by Paul Hamann, a German artist, in the early 1930s.

Major (later Sir) Desmond Morton, a member of Churchill’s intelligence net and a Chartwell neighbor.

F. W. Lindemann, “the Prof”—later Lon Cherwell.

PART FOUR

VORTEX

On the Saturday before Parliament’s Munich debate, Winston was at Chartwell, vigorously slapping bricks into place and awaiting a visitor, a twenty-six-year-old BBC producer, unknown then but destined to become infamous in the early 1950s. He was Guy Burgess, who with Kim Philby and Donald Maclean — all three upper class, all Cambridge men — would be cleared to review the U.S. government’s most sensitive documents, including the Central Intelligence Agency’s daily traffic and dispatches from Korea. In fact they would be Soviet intelligence agents. Burgess’s notoriety lay far in the future that sunbright morning, however, when Churchill, in a blue boilersuit (a forerunner of his wartime “siren suit”), left his bricks to greet his visitor, a trowel still in one hand. The meeting was purposeless; Winston had been scheduled to give BBC listeners a half-hour talk on the Mediterranean, but when the Czech crisis erupted he had asked that the program be canceled. Burgess was keen to meet him anyhow, however, and Churchill, feeling that was the least he could do, had agreed.

In the beginning he was gruff. He complained, Burgess recollected afterward, that he had been “very badly treated in the matter of political broadcasts and that he was always muzzled by the BBC. . . . He went on to say that he would be even more muzzled in the future, since the BBC seemed to have passed under the control of the Government.” According to Burgess, Winston said he had just received a message from Benes — he always called him “Herr Beans” — asking for his “advice and assistance.” But, he asked, “what answer shall I give? — for answer I shall and must. . . . Here am I, an old man without power and without party. What advice can I give, what assistance can I proffer?” Burgess stammered that he could offer his eloquence. Pleased, Winston said: “My eloquence! Ah, yes . . . that Herr Beans can rely on in full and indeed” — he paused and winked— “some would say in overbounding measure. That I can offer him. But what else, Mr. Burgess, what else can I offer him?” Burgess, usually garrulous, was tongue-tied. Moment succeeded moment, but he could think of nothing to say. He saw a great man, the scourge of fascism, caged by frustration. Then Churchill spoke. “You are silent, Mr. Burgess. You are rightly silent. What else can I offer Herr Beans? Only one thing: my only son, Randolph, who is already training to be an officer.”1

Throughout 1938 Churchill’s warnings had grown more and more persistent, and less and less effective. His mots were seldom passed along now because his targets, the “Men of Munich,” as Fleet Street called them, were believed to have prevented a general European war.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Afghan & Iraq Wars | American Civil War |

| American Revolution | Vietnam War |

| World War I | World War II |

Waking Up in Heaven: A True Story of Brokenness, Heaven, and Life Again by McVea Crystal & Tresniowski Alex(37018)

Empire of the Sikhs by Patwant Singh(22185)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(18086)

Hans Sturm: A Soldier's Odyssey on the Eastern Front by Gordon Williamson(16784)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(11919)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(10916)

Educated by Tara Westover(7078)

Tools of Titans by Timothy Ferriss(6965)

How to Be a Bawse: A Guide to Conquering Life by Lilly Singh(6701)

The Last Black Unicorn by Tiffany Haddish(5081)

Permanent Record by Edward Snowden(5007)

The Rise and Fall of Senator Joe McCarthy by James Cross Giblin(4852)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(4456)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(4427)

The Crown by Robert Lacey(4115)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4041)

The Iron Duke by The Iron Duke(3650)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(3270)

How to be Champion: My Autobiography by Sarah Millican(3193)