The Mobile River by John S. Sledge

Author:John S. Sledge

Language: eng

Format: epub, pdf

Publisher: University of South Carolina Press

Published: 2015-04-15T00:00:00+00:00

USS Hartford, circa 1900. Courtesy of the History Museum of Mobile.

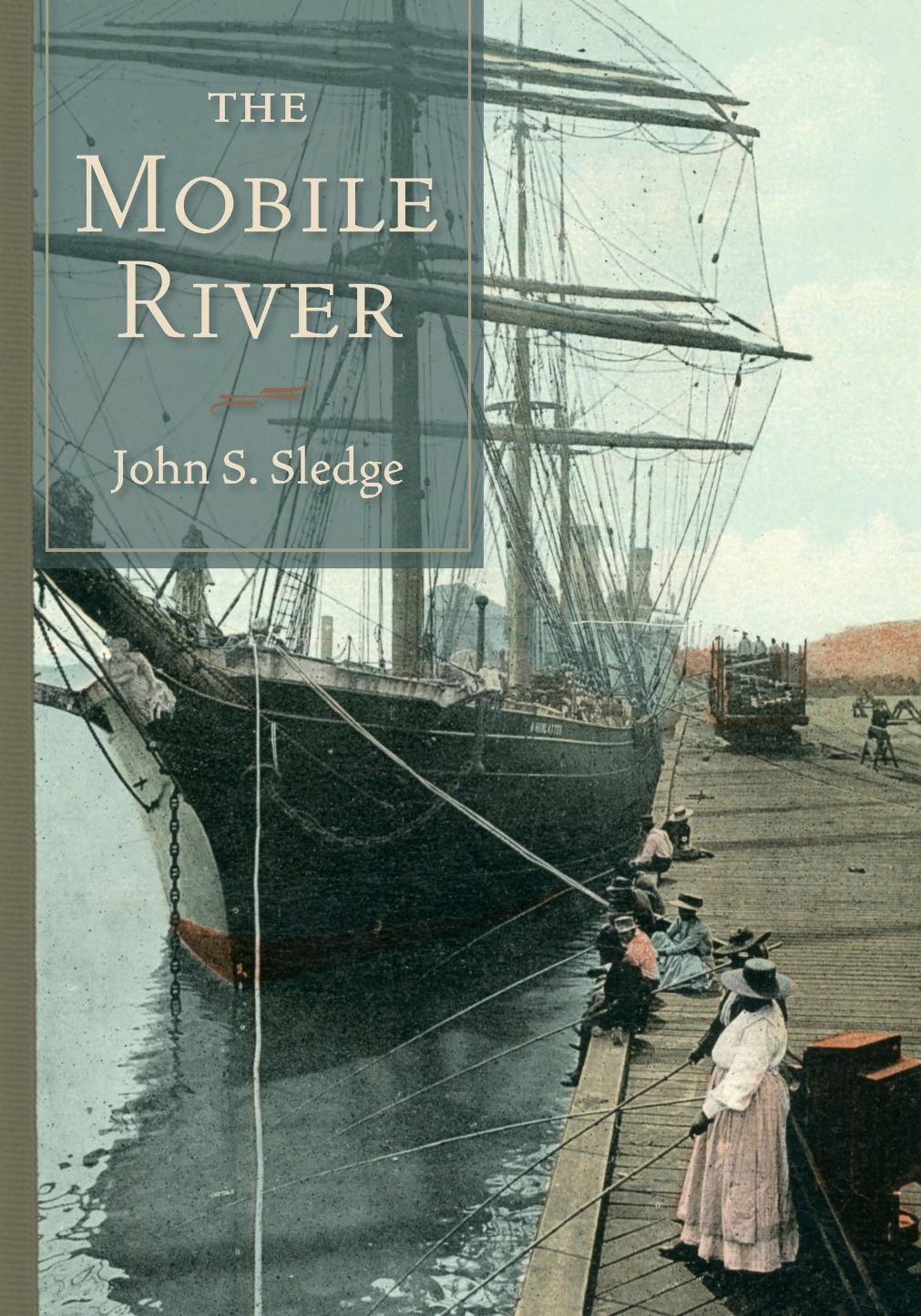

Front Street, circa 1895. Courtesy of the History Museum of Mobile.

One other dramatic change from earlier days was the near elimination of finger wharves crowding the shore. Much of the riverâs west bank was now controlled by larger corporate entities and the city, which used a combination of long marginal wharf berths with big open sheds and metal-clad warehouses punctuated by occasional piers and slips, better accessible by the oceangoing vessels that routinely called at the port. The L & N Railroad owned 2,200 feet up to Government Street that included a freight depot, passenger depot, and banana houses; the Mobile & Ohio Railroad had the section between Government and Dauphin, where the United Fruit Company had erected a long warehouse alongside the tracks. Abutting this property and extending northward 1,550 feet, a busy municipal wharf where the river boats called and the bay boats were berthed was maintained by the City of Mobile. Between Adams Street and One Mile Creek, the Mobile & Ohio Railroad had a grain elevator, an overhead conveyor, a coal chute, multiple cotton and hemp sheds, and eight angled piers divided by slips. At the harborâs northern-most reaches, near Three Mile and Chickasaw Creeks, was a concentration of sawmills, planing mills, and wood yards with log booms in the water to capture the thousands of cut trees sent downstream by delta swampers. No doubt Captain Reederâs experienced marine eye also saw and appreciated the plentiful and sophisticated ship-building and repair facilities, with dry docks, ways, foundries, machine shops, pattern shops, and salvage yards on both sides of the river. He would have found the harbor to be alive with vessels of every size and description, from the aforementioned stern-wheelers to barks, four- and five-masted schooners, oceangoing steamers, white-hulled âfruiters,â stubby-nosed harbor tugs, dredges, coal barges, fishing yawls, oyster boats, skiffs, and perhaps even a pirogue or canoe here or there, representing the oldest and surest means of Mobile River conveyance.2

And while cotton was obviously still an important aspect of Mobileâs trade, with factors and commission merchants scattered downtown, the port had diversified. Lumber, timber, coal, cotton, and cotton-seed oil were the biggest exports, while fruit (particularly bananas), sisal grass, coffee, mahogany, asphalt, and manganese and sulfur ores were key imports. Goods funneled into and out of the city by river and rail, though increasingly by rail, and local boosters rejoiced in a far-flung trade network that stretched from the north Alabama coal fields to the Midwest to Europe and Latin America. As these men adjusted their vests and checked their cravats preparatory to going aboard the Hartford to welcome Captain Reeder and his crew officially, they surely took great pride in how far their city had come since the war. The population, stagnant for decades, had begun to grow again and was north of forty thousand souls. The tiny mule-drawn trolleys of Victorian Mobile had given way to commodious electric cars, and many residents enjoyed reliable and labor-saving gas and electrical service.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Historic | Information Systems |

| Regional |

Man-made Catastrophes and Risk Information Concealment by Dmitry Chernov & Didier Sornette(4788)

The Revenge of Geography: What the Map Tells Us About Coming Conflicts and the Battle Against Fate by Kaplan Robert D(3614)

Zero Waste Home by Bea Johnson(3308)

COSMOS by Carl Sagan(2971)

In a Sunburned Country by Bill Bryson(2965)

Good by S. Walden(2932)

The Fate of Rome: Climate, Disease, and the End of an Empire (The Princeton History of the Ancient World) by Kyle Harper(2454)

Camino Island by John Grisham(2404)

A Wilder Time by William E. Glassley(2375)

Organic Mushroom Farming and Mycoremediation by Tradd Cotter(2319)

Human Dynamics Research in Smart and Connected Communities by Shih-Lung Shaw & Daniel Sui(2190)

The Ogre by Doug Scott(2135)

Energy Myths and Realities by Vaclav Smil(2078)

The Traveler's Gift by Andy Andrews(2026)

Inside the Middle East by Avi Melamed(1952)

Birds of New Guinea by Pratt Thane K.; Beehler Bruce M.; Anderton John C(1922)

Ultimate Navigation Manual by Lyle Brotherton(1778)

A History of Warfare by John Keegan(1734)

And the Band Played On by Randy Shilts(1635)