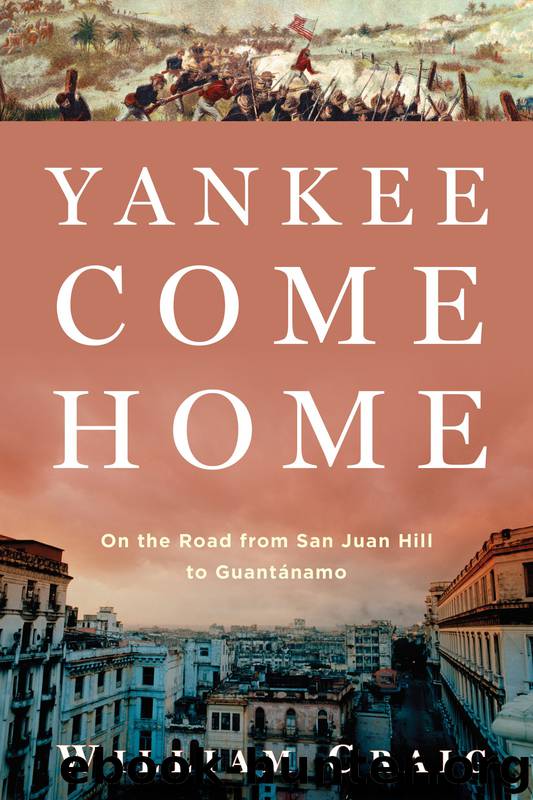

Yankee Come Home by William Craig

Author:William Craig

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Published: 2012-01-10T05:00:00+00:00

Chapter 9

HAVANA: DISMEMBERING THE MAINE

I’m not saying that tourists should avoid la Ciudad de la Habana, Cuba’s capital, the city once known as the Paris of the Americas.

Havana is an endlessly explorable wonder, a five-hundred-year-old New World cultural treasury. But it’s no more or less representative of Cuba than Manhattan is of the United States of America. Its interests are its own. The Cuban quintessences it emits are composed of raw materials—silver and sugarcane, sacred rhythms and revolutionary sacrifices, countless lives—drawn from all the island’s provinces, from Spain and West Africa, from Mexico and Morocco, and, yes, from Miami and Manhattan. Havana has imported aspects of itself from Shanghai and London, Hollywood and Moscow, and—despite its long demi-seclusion—still exports itself to the world, still markets a potent civic brand composed of optimism, vice, and valor: of antique cars rolling through florid decay, of music jazz-elegant and mambo-hot, of Che’s deathless guerrilla glamour. Havana is ruinous, fabulous, a monster angel with an outsize soul and a hard, hard heart.

So, yes, Havana is a must-see … but not if seeing it means you’re going to miss the rest of Cuba. If I had to choose between spending a week in Havana, touring the dusty Museum of the Revolution, drinking to Hemingway’s memory, and taking the obligatory stroll along the Malecón’s seawall promenade … and spending a week in the lush, hoodoo-haunted farmland of Pinar del Rio, in Camaguey’s sugarcane flatlands, or the mountain villages of the Escambray, I’d take any of those alternatives, knowing I’d experience more that is uniquely Cuban. And I’ve always stuck by Santiago, once the island’s capital and forever, in many ways, Cuba’s true hometown.

This time, because I was traveling as a freelance journalist, I was required to appear at Havana’s Centro de Prensa Internacional, the international press center, to register in person and obtain a special photo identity card. The card—expensive at sixty convertible pesos, almost eighty U.S. dollars—will supposedly help a journalist gain recognition and access, but in fact achieves exactly the opposite.

Cuba is a thoroughly totalitarian state, the kind of place where pointing your camera at a recognized tourist attraction—a statue or a street band—is permissible, but pointing your camera at, say, a watertank tower or a police station can get you hauled off for serious hassling or much worse. (It used to be impossible for Yanks and Brits to relate to this kind of experience, but not since 9/11.) Where paranoia is policy, going to extremes is the prudent approach. In a society like Cuba’s, identifying yourself as a journalist gets you informally but effectively barred, on a better-safe-than-sorry basis, from schools, factories, businesses, libraries, even museums. If I’d been foolish enough to wear my “pass” around my neck on my way into a restaurant, I’m guessing the odds are fifty-fifty I’d have gone hungry.

I’d traveled to Santiago before, as a newspaper reporter on a journalist’s visa, without having to make the Havana trek. But this time, as the CPI bureaucrats knew, I was staying longer, making a pilgrimage possible.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Vikings: Conquering England, France, and Ireland by Wernick Robert(77333)

Ali Pasha, Lion of Ioannina by Eugenia Russell & Eugenia Russell(39321)

The Vikings: Discoverers of a New World by Wernick Robert(36486)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(31340)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(30938)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(30894)

The Conquerors (The Winning of America Series Book 3) by Eckert Allan W(27904)

Empire of the Sikhs by Patwant Singh(22176)

Hans Sturm: A Soldier's Odyssey on the Eastern Front by Gordon Williamson(16700)

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(16641)

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(13877)

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari(13065)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(12938)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(11911)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(11896)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(11889)

Underground: A Human History of the Worlds Beneath Our Feet by Will Hunt(11263)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(11060)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(10914)